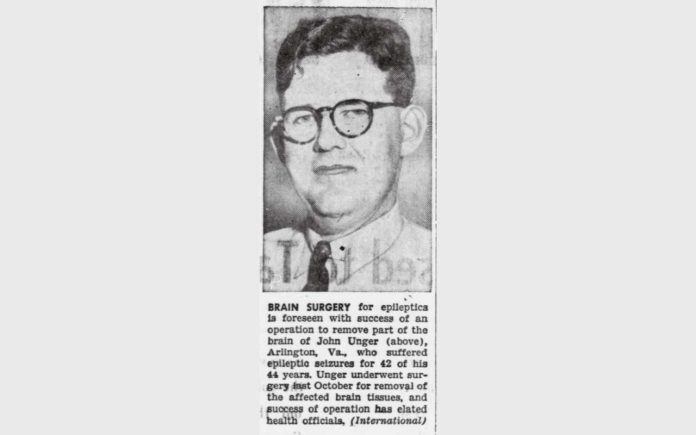

By the time he entered the operating room at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in October 1953, John Unger, Jr., had suffered from epilepsy most of his life. At 43 years old, he averaged about 100 seizures per year—roughly one every three days.

The worst year had been 1938, when the number reached 266. His mother scattered pillows around every room of their house in an attempt to protect her son from further injury during convulsions. Now surgeons were offering Unger a chance at deliverance—but it required removing a section of his brain.

Born in December 1909, Unger grew up in Arlington’s Old Dominion neighborhood, where he experienced his first seizure at age 2. Throughout his life, he tried numerous anti-seizure medications, with varying degrees of success.

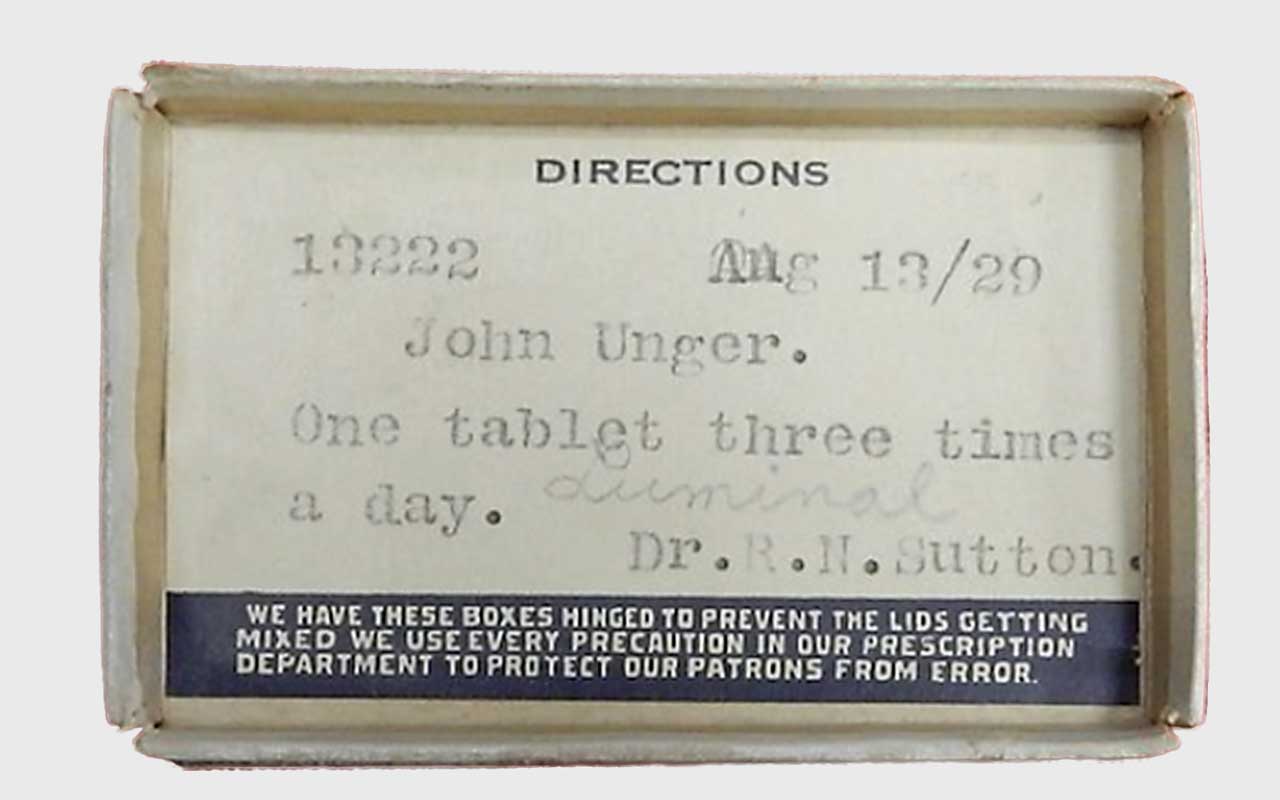

Among these was Luminal, the brand name for phenobarbital, first used as an anti-epileptic medicine in 1912. Luminal was still considered a relatively new treatment when Richard Sutton, a physician in Clarendon, prescribed it to Unger in 1929 with instructions to take one tablet three times a day.

By the 1950s, Unger was still living at home with his mother as his seizures persisted. The opportunity to undergo a temporal craniotomy—an experimental procedure in which a portion of his skull and affected brain tissue would be removed—was one he eagerly embraced, despite the risks. It would be the first such surgery ever performed at NIH.

“They told me that the operation would kill me,” Unger later shared in an interview with The Washington Post. “I [said] I wanted them to go ahead if they thought anything they might learn from me would help others.”

In fact, the craniotomy was an unmitigated success, completely relieving the Arlington resident of his symptoms. And over time, the pioneering procedure did help others. In the 13 years following Unger’s operation, some 400 patients underwent similar surgeries, an NIH newsletter reported, with more than half experiencing full relief. Variations of the procedure are still performed today, with a high success rate, as a treatment for epilepsy.

In 1966, Unger paid a thank-you visit to his NIH surgeon, Maitland Baldwin, in the spirit of “gratitude and friendship.”

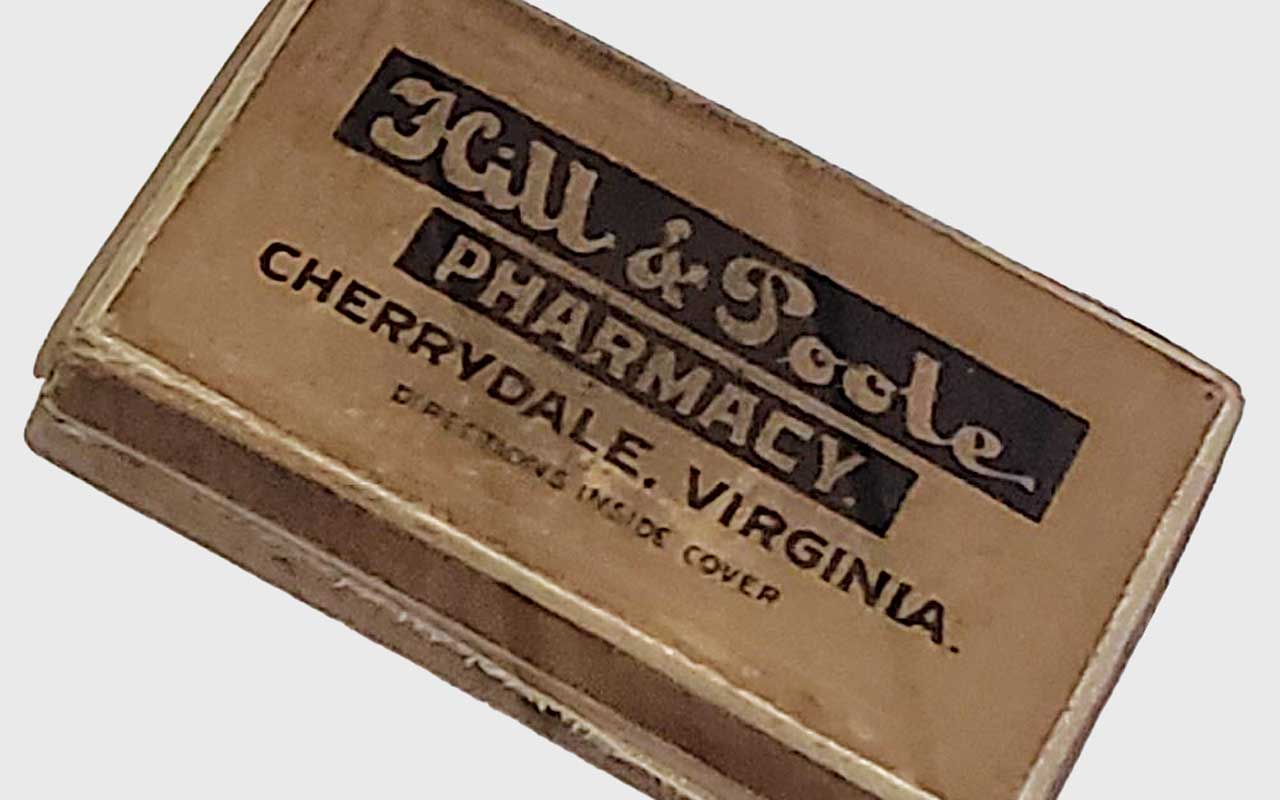

Unger died in August 1980 at the age of 70 and is buried in Arlington’s Columbia Gardens Cemetery. His Luminal pillbox from 1929, bearing the logo of the long-defunct Hill & Poole pharmacy in Cherrydale, is now in the collection of the Arlington Historical Society.