From the time she began receiving letter grades in elementary school to her graduation from Washington-Liberty High School last spring, Emma (not her real name) earned nothing but straight A’s.

As a college applicant, she looked dominating on paper, with an ACT test score of 35—just one point shy of a perfect 36—and a 4.6 grade point average, including advanced placement classes and a full load of international baccalaureate courses. She served in student government, played three sports (one as team captain), mentored her peers and volunteered her time tutoring elementary school students. She fired off 13 carefully crafted college applications and waited.

Then the rejection letters started rolling in: Duke, Vanderbilt, Princeton, Notre Dame, the University of Michigan. “You [start to] think that every college is going to reject you,” says Emma, 18. Her mom was just as bewildered: “What more could she have done?”

Emma’s experience is not so unusual. Northern Virginia is chock full of high-achieving parents whose high-achieving kids have set their sights on the uppermost echelons of higher education. They’ve taken the toughest classes, turbo-loaded their extracurriculars and sacrificed sleep to position themselves for success.

And yet legions of outstanding students who have seemingly “done everything right” are sifting through in-boxes filled with rejections. “They’ve cured cancer, they’ve climbed Mount Kilimanjaro… and they’re not getting in,” says Diana Blitz, an independent educational consultant and college coach with the D.C. firm The College Lady.

If those candidates aren’t receiving offers of admission, who is?

The Search for “Pointy” Kids

One tectonic shift inside the nation’s top colleges and universities is a preference for so-called “pointy” kids, says Kevin Carey, vice president of education and work at the nonpartisan D.C. think tank New America. After decades of courting well-rounded applicants, elite schools now want students who are the top of their game in just one or two areas. And we aren’t talking citywide chess champion or district all-star pitcher. They’re angling for students who have garnered state and national honors in that one thing—be it poetry, pole vaulting or extemporaneous speech.

“Colleges like students who have specialized and committed to something. They don’t want just a laundry list of 15 different things that somebody did a little bit,” Carey says.

Grace Lee, managing director of the virtual college counseling firm Command Education, notes that America has 26,000 high schools and therefore 26,000 or more valedictorians. Schools like Harvard, Yale and Princeton “could fill their classes 10 times over with people with perfect test scores, perfect GPAs, good activities and leadership skills,” she says. Elite colleges want “depth over breadth.”

They also have highly idiosyncratic slots they are seeking to fill, which tend to vary from one year to the next. A university with two senior cellists in its orchestra is going to be in the market for applicants with a bow. A dominant Division I soccer school whose attacking center midfielder is about to graduate will be recruiting to replace that position on the roster.

“The priorities of institutions change almost every year,” says Angel Pérez, CEO of the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC), a 28,000-member trade association based in Arlington. “It’s not as easy as saying, this GPA, plus this test score, plus this extracurricular activity equals ‘I’m in.’ It’s much more nuanced. That is why the process feels so opaque and frustrating to young people.”

Record numbers of applications—driven, in part, by test-optional policies and the advent of digital application portals like the Common App—also have left admissions offices flooded. In January, the widely used Common App reported a 7% increase in total college applications over the year prior. The nation’ No. 1 ranked university, Princeton, whose current acceptance rate is around 4%, received 32,836 applications in 2024, up from 26,247 a decade earlier, according to the website TopTierAdmissions.com.

That surge in volume has made coveted universities seem even more exclusive, Carey observes. A school whose acceptance rate dropped from 30% to 10% isn’t necessarily three times harder to get into for qualified students; it may simply be receiving a higher number of applications, while its student population stays the same. What’s changed is the ratio.

“It’s not actually harder to get into college,” he says. “It just sort of seems that way.”

Athletes, Legacies and Deans’ Darlings

Today’s college applicants have plenty of schools to consider. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the U.S. is home to nearly 4,000 degree-granting postsecondary institutions. Of those, fewer than 35 have acceptance rates of 10% or less, says Perez, a former head of admissions at Trinity College in Connecticut. The average acceptance rate nationwide is about 73%.

That hasn’t stopped competitive students from viewing this tiny subset of academia—Ivy League institutions such as Harvard and Yale, and other elite universities such as Stanford, Duke and MIT—as the Holy Grail. And yet the rationales behind admissions decisions at those schools remain somewhat of a mystery.

An acronym often tossed around by insiders is ALD—Athletes, Legacy applicants and “Dean’s Interest List.” That last item is shorthand for the rich and famous—the kind of wealth that might fund, say, a new sports stadium or research facility. A study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that 43% of white students admitted to Harvard in 2019 were athletes, legacy candidates, dean’s list darlings and, to a lesser degree, children of faculty members.

But the ALD formula seems to be shifting. Legacy applicants (children or grandchildren of alumni) don’t enjoy the same advantages they might have 20 years ago, says Blitz, whose company works with more than 150 families per year, including students from top-ranked high schools in the DMV. She says some universities have dropped legacy criteria entirely since those policies tend to favor upper middle-class white students.

And while it once was commonplace for university fundraising offices to flag the wealthiest student applicants in the pipeline, Pérez says schools have largely quit that practice, too.

However, recruited athletes continue to enjoy preferential treatment. They are “largely chaperoned through the admissions process by athletics staff,” Rick Eckstein, a professor of sociology at Villanova, wrote in a 2022 article for the nonprofit news site The Conversation. Those who apply early decision are “almost guaranteed acceptance and roster placement.”

Though Ivy League universities famously do not offer sports scholarships, a 2023 editorial in the Harvard Crimson noted that recruited athletes had an 86% chance of admission to Harvard, whereas the university’s general acceptance rate that year was around 3.4%.

Lee, of Command Education, estimates that roughly a third of the D.C.-area students admitted to the nation’s most selective colleges and universities today are recruited athletes.

How much does racial diversity come into play? Not much—at least not by the time admissions officers are reviewing individual student applications. A 2023 U.S. Supreme Court decision barred colleges from applying race-conscious criteria to offers of enrollment.

While admissions officers don’t know the race of the applicants they are reviewing, Pérez says efforts to cultivate diversity are happening farther upstream. Many colleges launch targeted recruiting efforts in racially and economically diverse areas to attract a wider range of candidates.

“The only thing you can control right now is the students that get into your applicant pool,” he says. “The more diverse your pool is, the more diverse your admit pool will be.”

The fact that wealthy families can afford private schools (or live in neighborhoods feeding top-ranked public schools) and pay for test prep courses, private tutors and essay coaches is not lost on universities. Pérez says admissions officers are often assigned to specific geographic areas so that they are evaluating applicants with similar resources from the same high schools.

Contrary to popular belief, colleges don’t have quotas for Northern Virginia, says Nancy Benton, owner of the Arlington-based consultancy Admissions Edge College Counseling. But they do strive for broad geographic representation in their incoming classes.

Arlington, being one of the most educated counties in the nation, has outstanding schools, families that value education and a surplus of impressive applicants. The same is true of Falls Church and McLean.

“It makes it particularly competitive to be applying to [certain] colleges from this area,” Benton says. “You just have more students that you’re competing against.”

The Fixation on Brand Names

As a member of W-L’s Class of 2018, Avery Erskine applied to eight colleges. She was rejected by six, including Duke and Northwestern—despite having earned straight A’s throughout high school while juggling a packed schedule of extracurricular activities. At first she blamed herself, wondering if heaping even more on her plate might have improved her chances.

Now 24 and an aspiring screenwriter in Santa Monica, California, she has two degrees from UVA (a bachelor’s and a master’s in English) and some newfound perspective. Her advice to others: Focus less on the name brand of the school and more on the fit.

“You’re not signing anything in stone when you are 18,” she says. “It will work out the way it should—not because of some great fate, but because you still are in charge of your life.” College is a beginning, she says, not an end.

Benton, whose company has advised some 250 college applicants over the last decade, agrees. “It’s not like the goal is to get into the college with the lowest acceptance rate,” she says. “The goal is to get into the college where the student will thrive.”

The fact is, most seniors applying to elite universities have strong grades and exceptionally high test scores, says Eleanor Monte Jones, owner of Rigby, a college consulting firm based in Annandale. “So that’s a baseline. That’s not a distinguisher.” She reiterates that colleges are looking for students who have pursued their interests in depth. For instance, a creative writing applicant who has taken every English class and submitted to literary journals, or a future nurse who has worked in a hospital.

Rather than applying to a laundry list of institutions with prestigious names, Jones advises students to target fewer schools, focusing on those that align most closely with their academic interests, values and lifestyle preferences. Like most college counselors, she advocates identifying a combination of “target, reach and safety” schools to ensure that they have choices.

In retrospect, “I don’t think any school with an acceptance rate below 30% can be called a target,” Emma says, given the number of applicants with similar bona fides applying to those same schools. “You can’t predict outcomes like that.”

Students aiming for the Ivies and other top-ranked universities—including specialized programs such as Juilliard or the U.S. Naval Academy—should also give serious consideration to just what it takes to get there, Jones says. The calculus isn’t unlike star athletes with dreams of sports scholarships, Olympic glory or a spot on the pro circuit. There are sacrifices.

“It requires a family and the child to make a decision as early as possible to position themselves for the most selective universities,” says Jones, who spent decades working in college admissions, most recently at Georgetown. “I’m talking probably seventh or eighth grade. That requires planning, that requires interest and it also requires aptitude.” Students interested in STEM subjects, for example, need to start accelerated math classes well before high school.

Lee’s company, Command Education, claims a 94% success rate in getting students into at least one of their top three choices. The kids she’s coached have put in the work, with achievements ranging from large-scale fundraisers to published research. One student designed an AI-driven technology platform to study music’s cognitive effects. Another 3D-printed prosthetics, which she then donated to families in South Asia. She turned down an invitation to the White House so she could attend prom.

Lee declined to share the cost of her services, noting that fees vary depending on the length of time spent with each student. But a five-day college bootcamp her company offered this summer in Arlington went for $10,000 per registrant. Blitz charges a flat fee of $8,800 per student, whether they need her services for one year or longer.

Alexandra “Allie” Vasquez had her heart set on Brown University until the rejection letter arrived with a thud in 2020. She remembers it being the first time in her life she fell short of achieving something she’d set her mind to.

With the Ivy League school off the table, Vasquez weighed the acceptance letters she’d received and headed for the West Coast. Now 23, she’s finishing up a five-year architecture program at the University of Southern California (which, it should be noted, had a competitive 16.5% acceptance rate the year she applied). Her high school GPA, which once seemed so important, is hazy, but she thinks it was a weighted 4.3.

In retrospect, Vasquez believes she landed where she was supposed to be. USC gave her space to explore different interests, and the vibe turned out to be a better match than Brown would have been. Arlington’s competitive pressure makes it far too easy for students to get caught up in the worship of certain schools, she says, and too easy for a rejection to feel like the end of the road instead of the speedbump it truly is.

“Everybody freaks out. I have friends who were incredibly good students who thought their lives were over, that they were never going to get in anywhere, not just into college, but in life,” Vasquez says. “It’ll pass. You will get an admission letter for somewhere, and it will feel like the sun has come out.”

Carey, who directs the education policy program at New America (he’s also author of the book The End of College: Creating the Future of Learning and the University of Everywhere), shares a similar perspective. “No one’s future depends on getting into their dream school as an undergraduate,” he says. “There are lots and lots of roads to opportunity. Have some sense of proportion of what the stakes are.”

For Emma, the sun eventually did come out. She heads to UVA this fall, where she plans to study computer science. The disappointment of those rejection letters has faded.

Her advice for others navigating the maelstrom of college applications: “You’ll end up where you should be. If you don’t, you can transfer. Be easy on yourself. It’s a hard process.”

Tough Competition

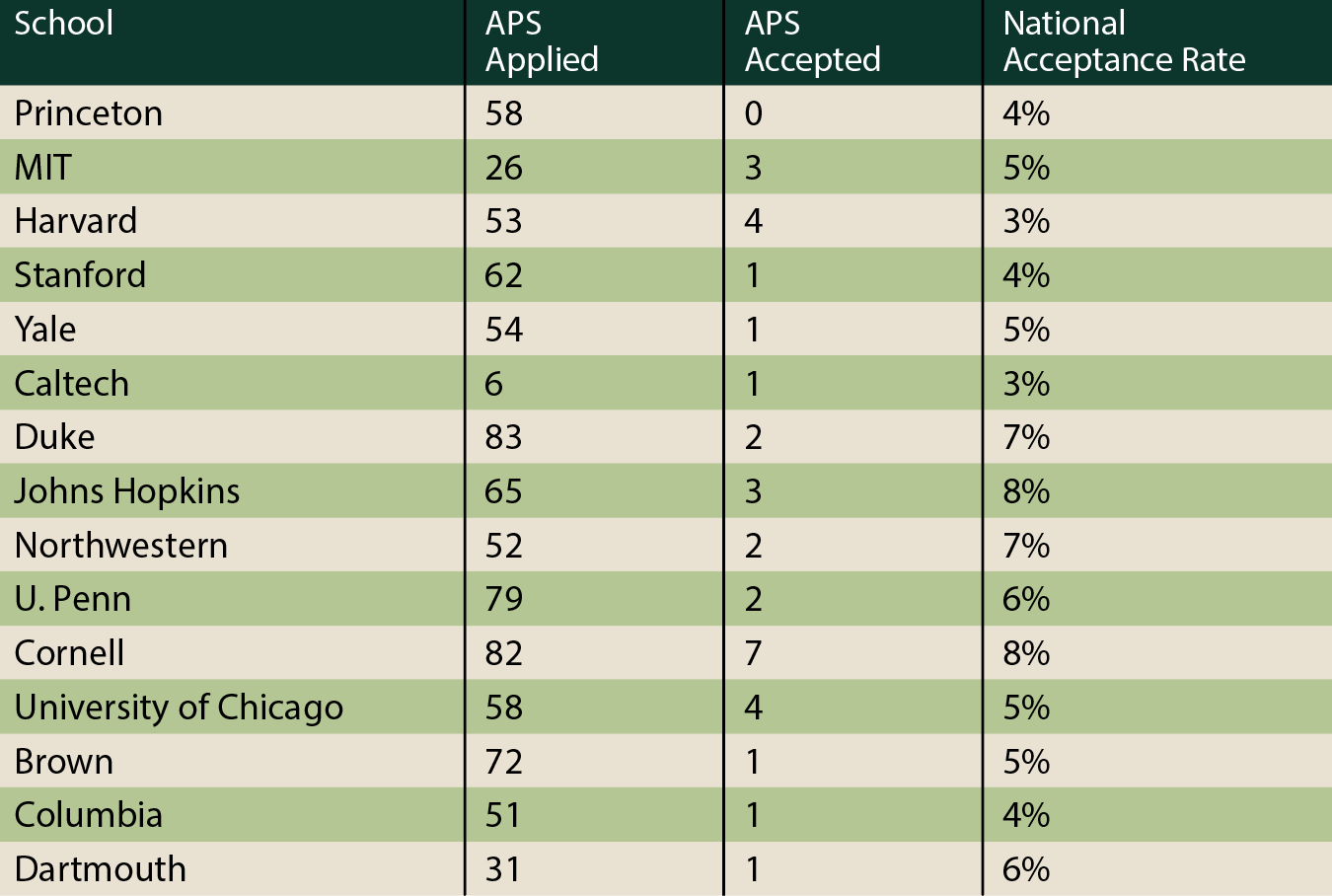

Arlington is known for its great public schools, but few APS graduates gain admission to America’s top colleges. Below are the 15 highest-ranked universities, according to U.S. News & World Report. The APS application and acceptance data were self-reported by Arlington students during the 2024-45 school year.

Deep Breath

- 73% students who apply to a four-year school get accepted, according to the National Association for College Admission Counseling.

- For applicants who find standardized testing challenging, there are 2,100 bachelor’s degree-granting schools that are test optional or test free, according to FairTest.

- Of the thousands of colleges and universities nationwide, fewer than 35 schools have acceptance rates of 10% or less.

- 90% of U.S. colleges and universities admitted at least half the applicants for the fall of 2021, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Business and education writer Tamara Lytle is an empty nester with twins in college. She lives in Vienna.