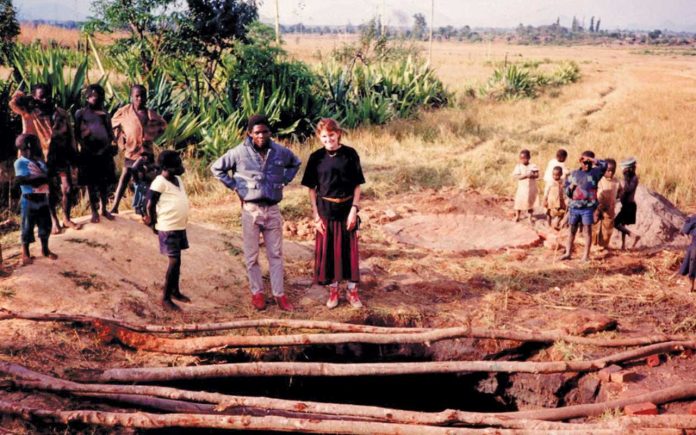

Before I arrived in Malawi in 1993 to work with the International Rescue Committee, I thought I understood what cross-cultural work meant. I had read the books, studied the theories and rehearsed respectful greetings in Chichewa. My uncle even developed a game for the whole family to play prior to my departure titled “Where is Malawi?” But none of that prepared me for what it would feel like to stand in a sunbaked village square, surrounded by people whose lives had been shaped by war, resilience and survival—and to try and teach them how to stay safe from landmines.

Malawi sponsored more than 1 million refugees from Mozambique during Mozambique’s 15-year civil war. During that time, more than 1,000 kilometers of the border between the two countries was embedded with landmines—in fields, near houses and on roads. The mines continued to put people on both sides of the border, especially children, at grave risk long after the war ended in 1992.

Working on a landmine awareness education program in this East African nation changed me, not just emotionally, but philosophically. It cracked open what I thought I knew about collaboration, identity and the meaning of impact. It showed me that human connection doesn’t rely on fluency in language, but fluency in effort, humility and shared purpose.

At first, the language barrier felt overwhelming. I didn’t speak fluent Chichewa or Portuguese, and many in the communities I worked with spoke little or no English. But something happened when we stepped into those village meetings. We used drawings, music, local translators, and sometimes nothing but eye contact and shared concern. And it worked. We found ways to communicate safety—how to identify landmines, what not to touch, how to report suspicious objects. The content was lifesaving, and the delivery through local theater was inspiring.

What saved me was learning that communication is about intention more than perfection. Respect, patience and listening can go further than fluent words ever could.

I was struck by the attitude of the communities. These were people who had suffered the unthinkable—displacement, death, mutilation—and yet they were not hardened. They were hopeful. Children who lived in camps still smiled when they danced. Elders who had lost loved ones still showed up to teach others what to avoid. Their resilience was not passive; it was active, gritty and deeply optimistic. It wasn’t just survival. It was a refusal to let despair define them.

That changed how I think about what’s possible. In the U.S., I’d often heard the phrase “Anything is possible,” but it felt abstract. In Malawi, it became real. I watched communities with little formal infrastructure mobilize, organize and implement public safety protocols. I saw people who had every reason to give up, choosing instead to persist. And I realized that possibility isn’t just a personal mindset. It’s collective. It’s what happens when people believe in each other, even when circumstances say they shouldn’t.

This experience forced me to wrestle with my own identity, too. At times, I wanted so badly to fit in—to not be “the American,” to be more like the people I was working with. I adopted local customs, ate nsima (the thick porridge that is a Malawi staple) with my hands, learned local idioms, and tried to listen more than I spoke. But even as I integrated into the culture, I came to a powerful realization: I would always be American. And that wasn’t a bad thing.

Instead of trying to erase who I was, I began to ask: What can I offer from my perspective? What can I learn from theirs? That shift—away from assimilation and toward integration—was liberating. It opened the door to real exchange. I brought my ideas and education, but I was just as much shaped by their lived experience and insight. We didn’t just teach each other; we built something together.

One of the most transformative lessons I learned was about how people can work across their differences. In Malawi, I met people with beliefs, lifestyles and worldviews that were far from my own. But when we worked toward the shared goal of landmine safety, those differences didn’t divide us. They made the work richer. We misunderstood each other, but we kept going. And in that messy, honest process, I saw what community really means: not sameness, but solidarity.

I came back from Malawi with a different kind of ambition. Not the kind that’s about climbing ladders or checking boxes, but the kind that’s about making change by connecting people. I continue building bridges across cultures, not because it’s easy, but because it’s the only way to drive meaningful impact in a world that’s more connected—and more divided—than ever.

Philosophically, I now believe in three things: First, that communication rooted in respect can transcend language. Second, that the most powerful change is collective, not individual. And third, that identity is not a barrier to connection—it’s a foundation for it, when held with humility.

Emotionally, I carry the faces and stories of the people I worked with. I remember the mother who showed up every day to help us teach others, even though she had lost a child to a landmine. I remember the boy who helped me translate not just my words, but my intentions. He showed me how to eat, bow and greet people, and also how to dance. In that way, I learned how to communicate, show partnership, show joy and allow people to sit and welcome me into dialogue. I remember feeling completely out of my depth—and then feeling completely at home.

Malawi gave me more than a chance to help. It gave me a new way to think, to feel and to live. It taught me that while cultural differences are real, they are not impassable. That impact is not about saving others, but about showing up, listening and working side by side. Most importantly, that optimism isn’t naive. It’s necessary.

I don’t romanticize what I saw or what I did there. The work was hard. The trauma was real. I left changed, not because I made a difference, but because they did—in me. And now, wherever I go, I carry that lesson: Anything is possible, but only if we do it together.

Gwen K. Young spent 11 years living on the African continent and more than 25 years focusing on humanitarian relief, international development and human rights initiatives in various African nations, working with organizations such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Medecins Sans Frontieres, International Rescue Committee and the Harvard Institute for International Development. Today she is the CEO of Women Business Collaborative. She lives on Columbia Pike.