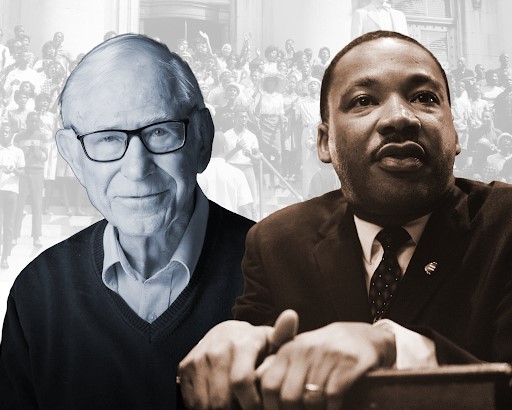

Most of us learned about Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream in history class. Robert McCan heard it from the man himself. Not at the Lincoln Memorial, but during a private conversation.

“I learned from Martin Luther King Jr. personally what his vision was, what his plan was, and I was committed to helping in any way I could to bring this to pass,” says McCan, who today is 101 years old and lives in The Jefferson senior residence in Ballston.

They met in 1955, when both were preachers speaking at an event on race relations at Vanderbilt University’s Divinity School.

Before their speeches, “we spent probably an hour and a half talking, and he told me what he was up to,” McCan says of King. “He told me that he was a pastor in Montgomery, Alabama, and that the week before there was a woman named Rosa Parks who had ridden on a bus, and she refused to go to the back of the bus when she was commanded by whites to do so.”

At the time, King was serving as president of the Montgomery Improvement Association, which led a boycott against the bus system.

“He explained to me how 60% of the riders of the bus in Montgomery were Black, and if all the Black people quit riding the bus, this would this would bankrupt the bus company,” McCan adds. “He would preach each night on racial justice, and they would plan for the next day for the boycott. They would try to get publicity for what was happening. Of course, he was a great speaker, and it was not hard to get the television stations in, first in Montgomery and then in Alabama and then across the nation.”

Clarity Through Experience

McCan grew up in Owensville, Missouri, in a devoutly Baptist family. He was a high school senior when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. Knowing he would be drafted, he decided as a freshman at Southwest Baptist University to enlist in the Navy through the V-12 program. That enabled him to stay in school for the duration of the United States’ involvement in World War II.

“When the war was over, I had been spared battle, and I felt a certain amount of guilt and a certain amount of responsibility,” he says. “‘To whom much has been given, much is required’ was a concept from the Bible. I decided I should be a peacemaker and a person who worked for justice in this society, because justice and peace are two sides of the same coin.”

One Sunday, McCan attended the Baptist Student Union convention in Columbia, Missouri, and heard Clarence Jordan, a white farmer, talk about a heated exchange he’d had with a Black man. Fed up with discrimination and brandishing a pistol, the man was threatening to kill the next white person he saw. Jordan offered to sacrifice himself. “The Black man put down his gun,” McCan says. This story of how one person could peacefully diffuse a loaded racial situation inspired him to enter the ministry.

“I hadn’t known an African American in my years growing up, because there was not one in our county, and it was well known that if any African American were ever to spend the night in our county, they probably wouldn’t live till the next morning,” McCan says. “At the same time, our church is preaching that God loves everyone. It never seemed to be a contradiction [to people] between what we were teaching and preaching in church and what we were living in the society. But I did see that contradiction.”

A History of Civic Commitment

After that meeting with King, several other historic milestones prompted McCan to become entrenched in the Civil Rights movement. One was the integration of public schools after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling. McCan was a church pastor in Clinton, Tennessee, when the town’s public high school was desegregated by court order in 1956.

A bomb destroyed the school two years later, and the students relocated to an unused elementary school in nearby Oak Ridge, the town where the atomic bombs used in World War II were built.

“I was invited to speak to the students and to the teachers,” McCan says. “I was there to talk about loving each other and working together and respecting each other and building a new world order. In the end, it really was a choice between loving each other and bombing each other.”

A few years later, McCan moved to Danville, Virginia, to serve as minister of its First Baptist Church. The town had a “tobacco plantation mentality,” McCan says. The mayor, who was an influential member of the church, pushed back against desegregation. In response, Black residents joined peaceful protests with King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which leveraged Black churches to fight segregation and disenfranchisement across the South.

On June 10, 1963—a day in Danville’s history dubbed Bloody Monday—McCan was there when the city’s police force attacked the protesters, arresting dozens and sending more to the hospital.

“I was fired from my job immediately because I had supported Martin Luther King” and integration, McCan says. He decided to leave the ministry in hopes of doing something with broader impact.

McCan’s Legacy

McCan returned to school—this time to Harvard—to become an academic administrator. In 1972, he founded Maryland’s short-lived Dag Hammarskjold College, named after the former UN Secretary-General, with a goal of fostering cross-cultural learning.

Twelve years later, McCan was instrumental in establishing the U.S. Institute of Peace to support the study, development and teaching of peacemaking strategies and conflict resolution.

“It was set up as quasi-public/private institution that would serve the public,” he says. “The people involved were mindful of their role to serve the public, but not to be the pawn of the president or any person. It was well on the road to becoming a very successful organization when Donald Trump came along.”

In December, the Trump administration renamed it the Donald J. Trump Institute of Peace. McCan views many of the president’s policies, such as those on immigration, as history repeating itself.

“I would call it blatant segregationist discrimination, overruling minority people and immigrants, along with African Americans,” McCan says. “All of this whole posture is a flashback to the days before Martin Luther King. I never thought we would be back in this, with these attitudes and positions and official government philosophies.”

Still, he holds fast to optimism: “I think the forces of acceptance, celebration and joy at diversity are more powerful in the end and will prevail.”