My husband and I recently joined another couple for dinner out in the Mosaic District. We were in a busy crosswalk when someone yelled, “Walk [expletive] faster!” It was the driver of a car waiting—apparently impatiently—for us to reach the curb so he could make a left.

The memory of that incident now lives rent-free in my head. My husband was mad. One of our friends wished the driver a more peaceful night than the one he seemed to be having. The other friend was stunned. And I thought, Well, that was rude.

The knot it created in my stomach reminded me of other episodes that left me feeling not so warm and fuzzy: the people we invited to our son’s bar mitzvah who didn’t bother to RSVP; the woman at the post office who assailed my children for laughing too loud; the store clerk who completed an entire transaction without speaking or even looking at me. I started to wonder: Are we getting ruder?

A Rude Awakening

By some accounts, yes. A November 2024 survey by the Pew Research Center found nearly half of Americans reporting an overall rise in rudeness since the pandemic. Of those, 20% said that public behavior has become “a lot more rude.”

Curious to know whether people living in and around Arlington shared these sentiments, Arlington Magazine in October posed the same question in an online poll. A significant majority (about 82%) of the 111 readers who responded said that civility has declined over the past five years. Nearly half said people have become “a lot more rude,” while 32% said we’ve become “a little more rude” as a society. One lone respondent said folks are more polite than they used to be.

The thing about rudeness, though, is that it’s hard to define because it can be subjective. What’s offensive to one culture or individual may be perfectly acceptable to another. What’s chivalrous to one generation may be perceived as sexist by another.

Parenting decisions are often a point of contention. Westover resident Cynthia Kilmer remembers being at a neighborhood bar on a Friday night around 10 p.m. when a fellow patron with a child in tow asked her friend to lower his voice and stop cursing. “My friend was like, ‘What? Your kid shouldn’t be here,’” she says.

Which was more offensive: cursing in public or bringing a kid to an adult-oriented place and demanding G-rated behavior? Depends on who you ask.

But some brushes with rudeness are undeniable. “We kind of know it when we see it,” says Linda McKenna Gulyn, a professor of psychology at Marymount University.

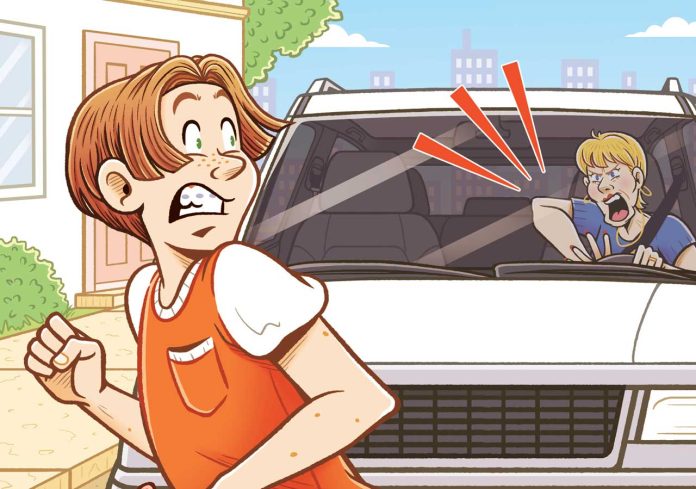

Oliver Hinson recalls getting honked at while waiting for a handicapped parking spot at VHC Health. “The people behind me couldn’t get around me for a minute,” says the Madison Manor resident. “This guy, he was just blowing his horn like crazy and called me the B word.”

Incidents in cars are a common flashpoint. Other participants in our survey were dismayed by what they perceive as an uptick in aggressive driving, inconsiderate parking and behaviors behind the wheel that endanger pedestrians. “Many drivers lay on their horn the moment a light turns green…as if any hesitation longer than a split second is an offense,” one respondent lamented.

Timothy Welsh of Baileys Crossroads remembers asking a woman in the passenger seat of a double-parked car if she would mind moving it so he could get by. “I got all kinds of expletives, and then it’s my fault that I confronted her,” he says. “That made me a little bit angry, but it also made me feel like I’m glad I’m not like that. I’m glad I’m thoughtful.”

McKenna Gulyn is not the first psychologist to observe that vehicles enable bad behavior. People in their cars think of other drivers not as humans, but as their vehicles. “I am my car, so I can cut someone off or do something even worse because it’s not you, it’s the car,” she says. “That person has been depersonalized. That person is a car.”

Uncivil Discourse

Many people interviewed for this story—including mental health professionals, everyday citizens and etiquette experts—blame the political climate for an epidemic of incivility. “I don’t think it’s Covid as much as national leadership discourse that is negative and disrespectful, which leads our youth to think it is appropriate,” one survey respondent wrote.

Psychology Today describes this as a form of social learning theory, which states that we take behavioral cues from the people around us.

Partisan rhetoric and attacks, distilled into sound bites and memes, have normalized a language of disrespect and contempt. (In November, the President of the United States chastised a reporter for asking a question he didn’t like by responding, “Quiet, Piggy.”)

To the surprise of no one, many survey respondents described the internet as a hellscape of incivility. “The rudeness I see is not in person,” one person wrote. “It’s when [the offender] can hide behind what they say on the phone, on social media and in emails.”

Falls Church resident Pamela Lessard concurs. “People feel like they have permission to just vomit nastiness in any kind of situation where comments are available,” she says.

The fact that rudeness attracts attention makes it downright compelling to some. “The more you’re able to be outlandish via social media…that is what almost makes us famous now,” observes Crystal L. Bailey, founder of the Etiquette Institute of Washington. She teaches classes on etiquette at Arlington County public schools and hosts workshops for kids, adults and corporations.

So what is it about Facebook, X, TikTok, Nextdoor and other social media platforms that brings out the worst in us? As with vehicles, the internet imparts a layer of anonymity. Some people use online pseudonyms and avatars, making it even easier to dissociate from the recipients of their ire.

“That anonymity allows people to get away with being pretty awful to one another,” says Jill Weber, a McLean psychologist whose expertise includes treating individuals struggling with (among other things) emotional regulation, anger management and impulse control. Social media also fosters a tribal mentality that feeds divisiveness, she adds. “If you see 10 other people who are upset about something, you just hop on that train and everybody attacks.”

Navigating the digital realm can be treacherous. In a 2021 Pew study, 41% of internet users claimed they’d been harassed online. A whole vocabulary now exists to describe various forms of rudeness on social media, including ghosting (ending communication without explanation), trolling (posting inflammatory or derogatory comments) and doxing (revealing personal information to exact revenge or make an individual feel unsafe).

Even folks who use their real identity may behave differently online than they would face to face. McKenna Gulyn says that feeling of anonymity or group think can erode the sense of self that guides in-person interactions. Social psychologists refer to this phenomenon as deindividuation.

“When you are online and someone says something in a chat and you don’t like it, you can say, ‘That’s stupid,’” she says. The problem is, those behaviors are creeping into offline interactions. “I think it becomes habitual, and it gets transferred into the real world.”

Impolite Society

Some would argue that public decorum has fallen by the wayside. Participants in our survey reported entering buildings behind people who let the door close in their face. They bemoaned a lack of eye contact with store clerks and receptionists. They’ve seen customers demeaning service industry workers, and the ugly emergence of a “me first” mentality.

Caryn Leslie recalls feeling frustrated and invisible when she arrived promptly for lab work at her doctor’s office, only to wait while the technicians finished gossiping about a coworker. “I’m standing there waiting for them to acknowledge me, and they’re just chatting away,” says Leslie, who lives in Douglas Park. “It was almost as though they resented that I was standing there. You don’t want to say, ‘Excuse me,’ because then they get all huffy about it. It just makes for an uncomfortable situation.”

Cici Schultz, a resident of Arlington’s Overlee neighborhood, was appalled when she witnessed a man berating a teenage cashier at the grocery store for using the wrong bags. “That poor 17-year-old was thinking they were going to get fired,” she says.

The apparent prevalence of such attacks jibes with research conducted by Christine Porath, a professor at UNC’s Kenan-Flagler Business School and author of Mastering Civility: A Manifesto for the Workplace. A 2022 survey of people in customer service jobs worldwide found 73% saying it wasn’t unusual for customers to behave badly, up from 61% a decade earlier.

In a recent article for Psychology Today, Susan Krauss Whitbourne, a professor emerita of psychological and brain sciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, posited that maybe people aren’t ruder than they used to be. Perhaps the current crop of bad behavior is just more public. Nine in 10 Americans own smartphones, and they’re apt to use them to record and document unsavory human interactions.

People would do well to remember that “every single person around you has a 4K-capable phone, capable of taking video, capable of live streaming to the internet,” says Reed Albers, who lives in Bristow and works in the Arlington office of the Virginia Family Law Center.

Cultural Contagion

There’s a price to pay for rudeness, even if you aren’t the aggressor or the recipient. Research published in the Journal of Applied Psychology suggests that merely witnessing others’ rudeness can have a negative effect on mood and cognitive performance. “It definitely increases stress, or it could lower your concentration [if you are] ruminating about the interaction,” says Zack Goldman, owner of Solid Ground Psychotherapy in Arlington. Watching stressful interactions unfold also “erodes trust in people in general and leads to more of this dehumanizing cycle,” he says.

What’s more, rudeness can be contagious. Researchers at Lancaster University in the U.K. have even coined a term for this phenomenon: the Principle of (Im)politeness Reciprocity.

Marymount professor McKenna Gulyn describes the contagion as a form of “excitation transfer”—the notion that arousal from one stimulus makes us likelier to respond emotionally to another, unrelated one. For example: “You have an argument with your mom in the morning…and then you go to a public setting and you’re rude to the clerk,” she says. “It’s nothing to do with the clerk. It’s because you’ve taken that emotion and you’ve found another target for it. Is that target really deserving of that? Probably not.” (A similar term used by psychologists to describe this tendency is “displacement theory.”)

Goldman contends that rudeness is rarely intentional. He considers it a stress response, not a personality trait. “People act rudely when their emotional regulation skills break down and they’re trying to gain more control or protect themselves,” he explains. “It’s almost a reaction vs. something that’s deliberate and thought out. It’s something that happens impulsively.”

When it comes to social norms, there are degrees of bad behavior, says Rebecca Czarniecki, an etiquette coach and owner of Tea with Mrs. B in Falls Church. (Her company hosts tea parties and manners classes for children and adults.) Sometimes a faux pas—for example, failing to thank a party host or gift giver; blaring music with the car windows down; talking loudly in the library; disregarding a restaurant’s dress code—happens simply because that person doesn’t know better.

“When someone does not have good manners, [it may be that] they’re just not aware,” she says. “It’s really no different than having to perform in front of an audience and never picking up the instrument or practicing. When I think of rudeness…it’s a loud, abrupt interruption into the dance of life.”

Empathy Falling

McKenna Gulyn sees a correlation between rudeness and an overall decline in empathy—the ability to put yourself in someone else’s shoes and relate to how they are feeling. “We need to find a way to reconnect and re-energize each other in order to restore that sense of the world is still an OK place,” she says.

McLean psychologist Weber believes tangible, in-person interactions are an antidote: “Research shows that we do better when there’s actually a connection, even if it’s a small connection, even if it’s small talk. That floods our nervous systems with the good chemicals that make us feel like we belong and we’re a part of something.”

According to Pete Davis, a civic advocate and filmmaker based in Falls Church, community reengagement is another step in the right direction. Join or Die, the 2023 documentary he made with his sister, Rebecca, (and based on a book by retired Harvard University professor Robert Putnam) illustrates the importance of social capital—the value that comes from social relationships, generalized reciprocity and doing something for the greater good, rather than personal gain.

Technology was making us more isolated even before the pandemic, he says. In a 2017 study by the Pew Research Center, 43% of respondents nationwide said they belonged to no community organizations.

Davis thinks a renewed commitment to community service could be restorative. By joining clubs, “you learn the civic skill of being a social person who can interact with other people in public,” he says. “You’re also building up a cultural sense that the public matters, that any given person in your neighborhood is part of your community and therefore you should treat them well.”

Rudeness may be a societal scourge, but stopping it requires personal effort. There’s self-awareness involved in recognizing when your state of mind makes you more prone to being rude yourself, or to taking others’ actions personally. Arlington therapist Goldman recommends mindfulness exercises to enhance that self-awareness. Mindfulness teaches you to notice when your thoughts drift so you can bring them back under control.

Taking responsibility for your own actions is another step toward civility. When you’re rude, Weber says, own it and apologize. “Tell the person on the receiving end, ‘I know this isn’t your fault,’ or ‘I’m having a really bad day.’”

And if you bear witness to another person’s rudeness? Politely call that person out or let the victim in the exchange know that the aggressor’s behavior was wrong. Schultz says that after the grocery store customer yelled at the young cashier, she told the teen, “You’re doing a great job.”

Arlington resident Hamilton Humes likes to give folks the benefit of the doubt. As a rule, he assumes that most impolite actions stem from cluelessness, not intentionality. Instead of confronting people who are behaving poorly, he likes to thank those who are not. “People respond more to positive feedback, and if you encourage good behavior, that crowds out bad behavior,” he says.

Lastly, forge connections to flex that empathy muscle. The pandemic made a lot of interactions more transactional, Weber says. “I need this person to give me X and then I’m going to move on and get back into my orbit vs. really trying to make eye contact and connect and try to understand a little bit about their perspective. All of those things are harder if you’re not in the practice of [doing them].”

Ultimately, says McKenna Gulyn, we all want the same thing. “We all want to be respected and loved and to be seen as human.”

Stephanie Kanowitz is a digital editor at Arlington Magazine and mom of two kids who always send thank you notes after receiving gifts.